Over-practicing is often negatively connotated due to people thinking it’s practicing too long or that the practice is not effective anymore. This is only partially true, as advanced musicians are able to practice for lengthy amounts of time while still practicing good quality.

In an experiment conducted by music psychologists Edoardo Passarotto, Florian Worschech and Eckart Altenmüller, the relationship between practice, performance anxiety, and the risks of playing-related injuries was analyzed.

According to their publication on Frontal Psychology, “…Training protocols specifically aimed at improving practice effectiveness and reducing music performance anxiety, [prevents] playing-related injuries in musicians.”

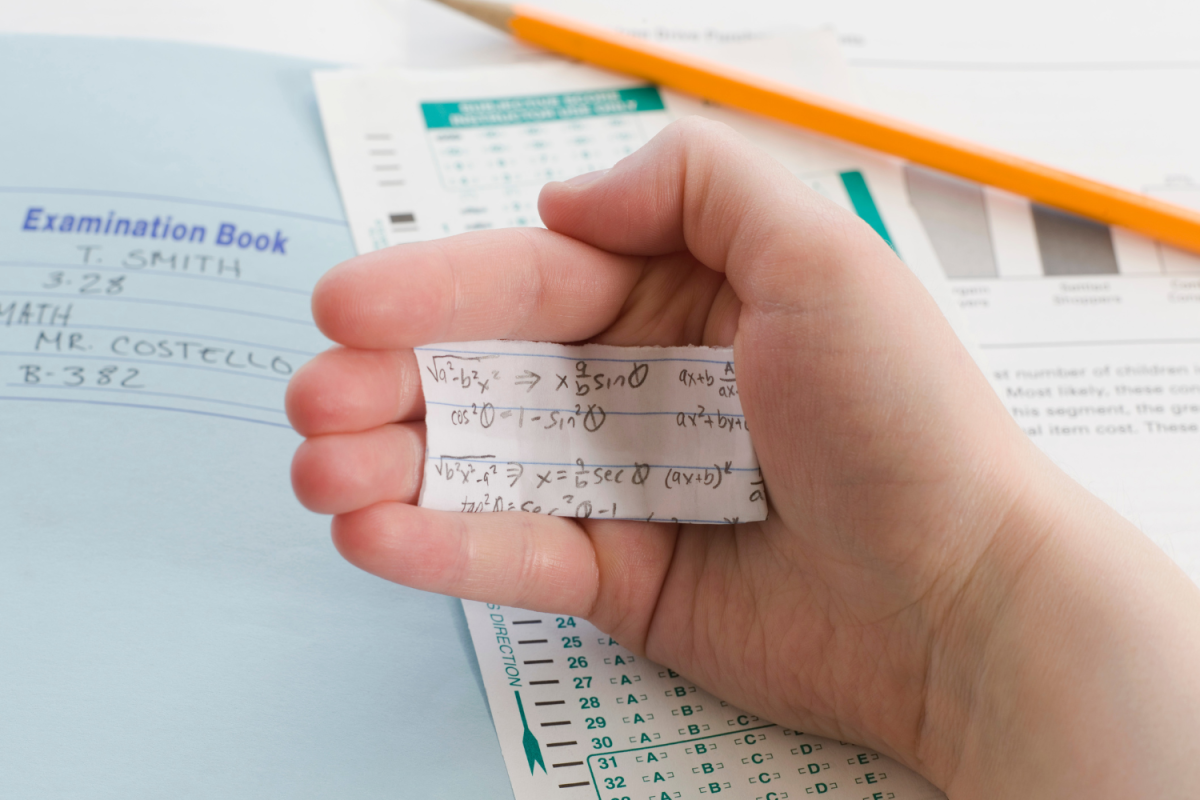

The study enlisted a group of young adult right-handed pianists to play leaping chords on a digital keyboard. The scientists measured the players’ error rate as they repeatedly practiced the intervals.

Interestingly enough, some groups increased their error rate after practicing. After the music psychologists observed this, the researchers suggested that heightened anxiety may have contributed to this phenomenon, with less anxious individuals demonstrating a lower likelihood of injury, provided they practice with care and effectiveness.

So musicians can over-practice, but some with anxiety potentially get injured. The most commonly known reason for performance anxiety is simply to play well in front of an audience.

Tenor saxophonist and piano experimentalist Trinity Kimbrough (12) has experienced this very thing. She was preparing for a recital, practicing for perfection, until her injury happened.

“I was not hitting the notes…it was making me really mad. I was like, I need to do this so I can do this solo,” Trinity said.

After stressful training, Trinity experienced tendinitis, cubital tunnel syndrome, and carpal tunnel syndrome.

“I hurt my arms and I couldn’t play for like a year,” Trinity said. “I got my injury two years ago, and I still have problems.”

The aftermath of her intense training resulted in enduring physical issues, preventing her from playing for nearly a year. There is a fine line between dedication and mindfulness.

Another musician, Liang Lim (10), began his musical career in the third grade at Mizzou’s String Project.

Although he was not initially a fan, after taking private lessons from teacher Kirk Trevor, things took a shift.

“He taught me an ambulance thing on cello and then promised me cookies, so I started liking cello,” Liang said.

All of these student musicians shared something in common–they had a goal in mind when practicing. Whether it was an important performance coming up, intentions of mastering a technique, or a cookie incentive, these musicians wanted something.

“I have a strong desire to get good scores on Federation and MMTA competitions,” Liang said.

Federation and the Missouri Music Teachers Association are competitions outside of school that many private lesson teachers in the community recommend.

A research paper by Katie Zhukov from the University of Queensland stated that expert musicians “spend a great deal of time in a concerted effort to improve their playing,” and that “high achievers tend to participate in many other musical activities.”

Another String Project cellist also was injured, but they had a different take on practicing.

Only a freshman, Mackenzie Moyer is currently a member of the Wind Ensemble band and Camerata orchestra at Hickman, both being the highest programs offered. To this day, Mackenzie still finds herself in shock.

“I don’t know how I got into [the] top band. I’m gonna be completely honest…Because I bombed the audition,” Mackenzie said.

As a modest six-year player, Mackenzie claimed she practices an hour and 45 minutes on the daily.

“I started practicing more because I wanted to get better. And then eventually, I think I got good enough that I didn’t need to practice as much for the music that I was playing,” Mackenzie said.

She practices, plays, and performs for herself, not necessarily for others.

“I’ve injured myself in a practice one time but it wasn’t because I over-practiced, it was just because I hit my thumb. I did a really bad shift…and then I have a scar,” Mackenzie said.

An injury from a year ago, like Trinity’s, still affects Mackenzie.

With the strict performance culture in vast areas of extracurriculars—in this case, encouraging aspiring musicians to hone their skills—it is important to advocate for the embracement of progress without sacrificing one’s well-being.

Over-practicing is not the issue. It is the lack of understanding that perfection is in the technical progress gained from each practice session, not in the amount of time spent practicing.

As for advice for those who feel pressured to practice with an arguably negative attitude, Mackenzie said, “Practice what you want to, not what you’re assigned.”

And if a student ever feels sore after practicing, they should “talk to [their] teacher,” according to Liang.

Haley Carrier • Feb 29, 2024 at 12:28 pm

I enjoyed the insight you provided to specific musicians at Hickman. I haven’t seen the study of pianist accuracy, although I do believe the results when the intervals are missed after continued practice. It’s probably not possible, but I would love to see a follow-up article further in the future showing how these same musicians deal with their injuries in a professional setting of college or specific ensembles.