English at school, broken English at home. Rich melanin, fair skinned. Kinky hair, straight hair. American jewelry, Kenyan jewelry.

Growing up biracial, Sophomore Caiden Ferguson has a long journey of defining himself. The clear duality between American culture to his parents’ culture brought confusion. Social norms such as behavior and beliefs and tangible things like cuisine and music taste differed strongly. Behind all this was a more visible indicator of self-identification.

“My parents don’t look anything like me,” Caiden said.

Caiden Ferguson is biracial with a Nigerian father and Caucasian biological mother.

“Both of my parents never really understood what I went through as someone who is multiracial, and that can be difficult [and] no, it was. It was really difficult to speak up about it, because, you know, I always thought that they [wouldn’t] understand how I see from a different light,” Caiden said.

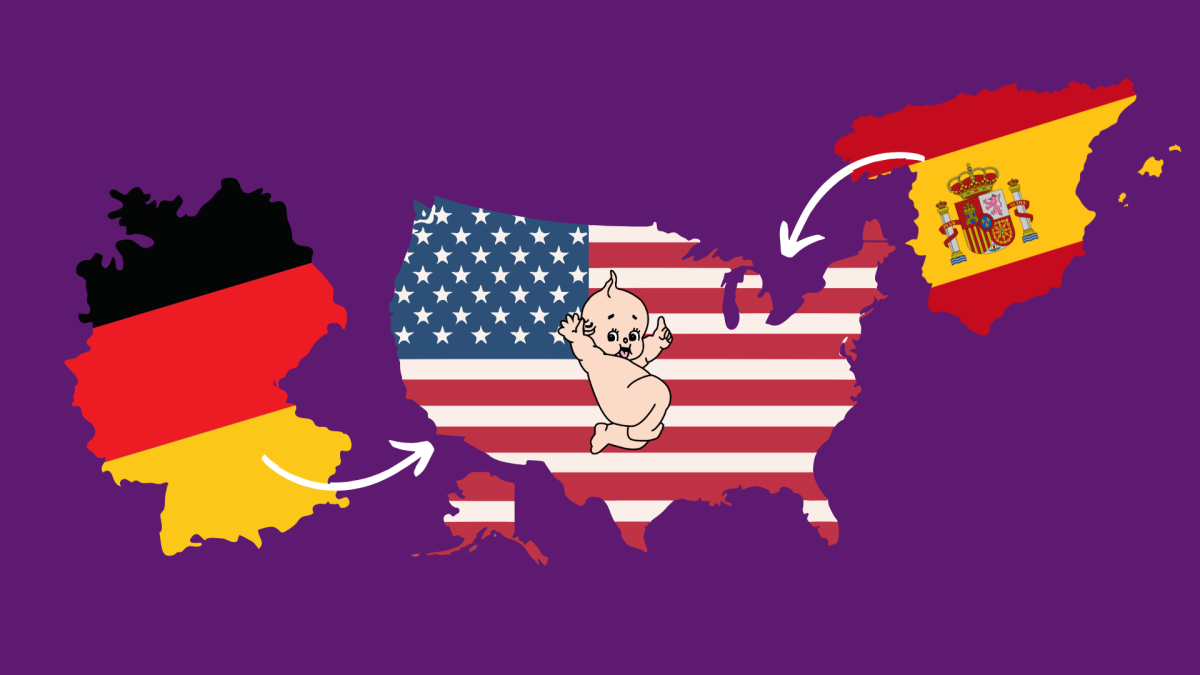

Caiden’s identity crisis began with his complicated generational status.

His grandparents came to Columbia before his dad was born. When both parents are native born, the child is classified as third- generation. However, Caiden’s circumstances were unique.

After his dad was born, he moved to Nigeria as a child.

“[He was] so young to the point where he can’t even remember memories [in Columbia],” Caiden said.

The closest category for Caiden’s case is a two and a half generation immigrant, as one parent was born in the United States and the other being a one and a half generation immigrant.

“That’s kind of also why I struggled with identity. Like, if I still identify as being half Nigerian, since my dad was born here, what does that still make me, like, completely American, or does that make me African American?…When I found that out from my dad, it was kind of awkward…With the identity crisis that I already had from childhood, it kind of just added on to it,” Caiden said.

Caiden’s first language is English. For both Caiden’s dad and step-mom, English is not their first language.

His dad has been trying to teach him his native language: Hausa. It is a chadic language, a part of the Afroasiatic language family.

“It’s been a learning curve, for sure, because this is the first time that I’m living with them full-time,” Caiden said.

Learning multiple languages had one obstacle: time.

“With my stepmom, it’s been more difficult with her work hours and my school hours trying to teach me how to speak her native language, which is Swahili and Luo. Since she gets off of work later than I get off of school, I don’t really see her that often,” Caiden continued.

Since childhood, it has been difficult for Caiden to place himself in a group.

“My biological mom was white… I feel like it just made it difficult to truly identify myself with certain ethnic groups, because there’s one side saying, Oh, I’m too light-skinned, or oh I’m too dark-skinned. I didn’t really know where I belonged,” Caiden said.

He started to notice the physical differences between himself and his Caucasian friends.

“They would put their hair up in certain hairstyles. Then I was like, Wait, why does my hair look different from theirs or why does my skin look darker than theirs? It was really dehumanizing and demoralizing,” Caiden said.

His friends began to notice differences as well.

“They would be, like, touching up on my hair and stuff, and that made me feel some sort of way,” Caiden said.

These instances of hair touching and head patting continued.

“I told them to stop, because that was just not how I roll, [but] they didn’t stop,” Caiden said.

Caiden’s friends would ask why his hair texture felt drier than others.

“It just really, really hit hard hearing that from a friend,” Caiden said.

Looking back on it, he is more understanding of his friend’s curiosity.

“We were just kids, so it’s not like they’re doing it on purpose because they just didn’t know that,” Caiden said.

This was the root of his identity crisis growing up, but it was also the start of learning how to be comfortable in his own skin.

“There’s always going to be people that are going to be telling you, oh you’re this or oh you’re that. Don’t listen to them,” Caiden said, “The only thing that matters is what you identify as and how you see yourself. So whether somebody’s telling you this or that, it shouldn’t matter what they think. It should only matter what you think of yourself as a human being.”

As grade school progressed, his friends did too. They have now helped Caiden navigate self-definition.

“They don’t see me for race, they just see me as a person, just a regular human being. Just because I’m mixed into multiple ethnic groups, it doesn’t always define me as a person,” Caiden said. “Don’t let other people define you.”